The low hum of the cooling system filled the room as engineers at Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) reviewed thermal test data. It was late October, and the pressure was on. The company, aiming to demonstrate net energy from its SPARC fusion device by 2025, felt the heat – not just from the experiments, but from the geopolitical realities of the fusion race.

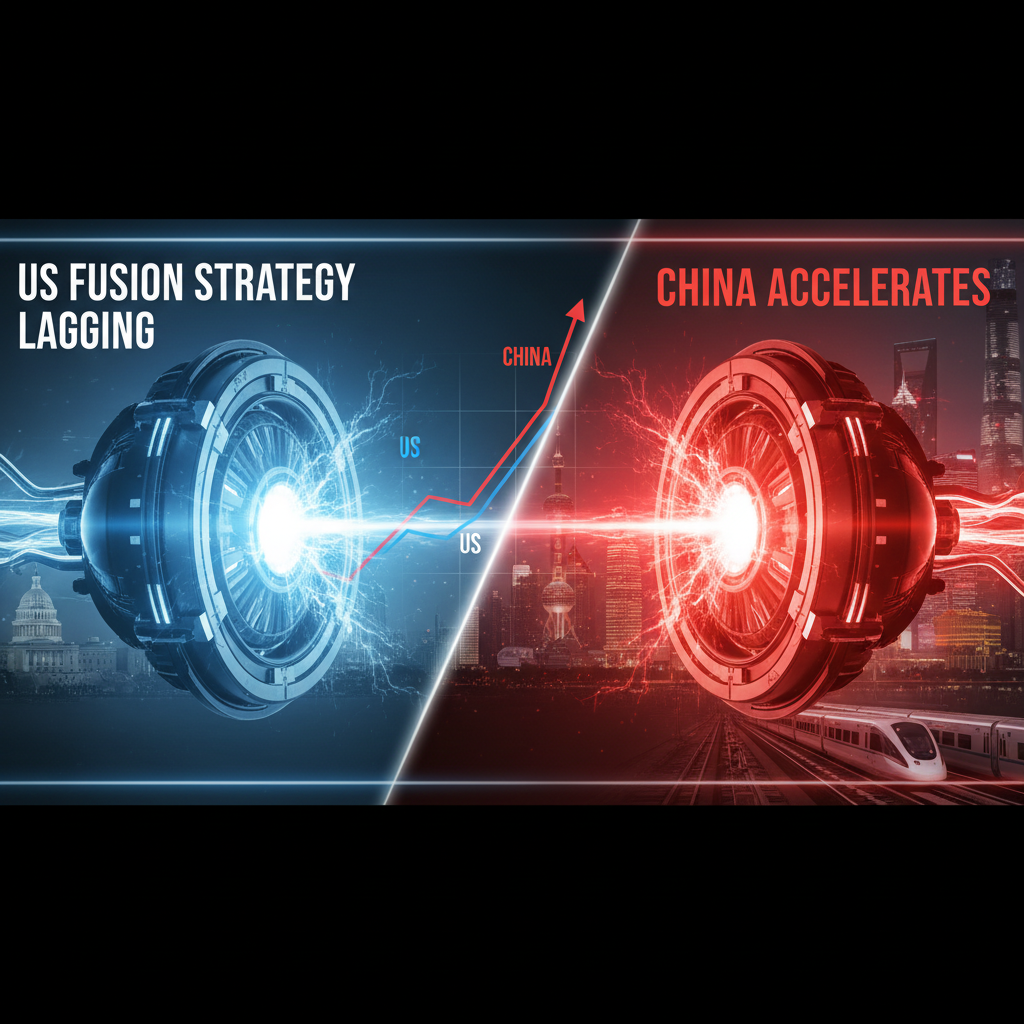

Bob Mumgaard, CEO of CFS, speaking to FOX Business, didn’t mince words. He framed the situation as a potential “Sputnik moment.” China, he warned, is rapidly advancing its fusion energy development, potentially leaving the U.S. behind. The stakes are immense: a leading position in fusion could translate into energy independence and a technological edge for decades to come.

The U.S. strategy, Mumgaard implied, is stuck in the past. While the Department of Energy continues to fund research, the pace of development isn’t keeping up with the rapid advancements coming out of China. The details are hard to come by, but the whispers in the industry suggest Beijing is pouring significant resources into its fusion programs. This includes government funding and, crucially, a streamlined regulatory environment that allows for faster progress.

“The Chinese are playing a different game,” said Dr. Emily Carter, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton, during a recent industry conference. “They’re not just funding research, they’re building. They’re investing in the infrastructure needed to commercialize fusion, from materials science to reactor construction.”

This sentiment is echoed by analysts. A recent report from the Breakthrough Institute suggests that China could achieve a commercially viable fusion reactor within the next 15-20 years. That’s a timeline that would put them ahead of many U.S. projections, which often cite the 2030s or even later for commercial viability.

The challenges for the U.S. are multifaceted. Export controls and supply chain issues are significant hurdles. The U.S. government’s restrictions on advanced technology exports, intended to limit China’s access to critical components, also inadvertently hamstring domestic companies. Companies like CFS must navigate a complex web of regulations, which can slow down progress. Meanwhile, China’s domestic procurement policies favor Chinese suppliers, giving their fusion projects an advantage.

The manufacturing side is equally complex. The U.S. relies heavily on TSMC for advanced chip manufacturing, but China has been rapidly developing its domestic chip-making capabilities through SMIC. The implications for fusion energy are significant, as advanced chips are crucial for controlling and monitoring fusion reactions. Any lag in chip development, whether due to supply chain issues or policy, could set back the U.S. fusion efforts. Or maybe that’s how the supply shock reads from here.

The conference call with CFS investors was tense. The Q&A session was dominated by questions about timelines, funding, and the competitive landscape. Mumgaard, while remaining optimistic, acknowledged the headwinds. He emphasized the importance of public-private partnerships and the need for a more aggressive approach to commercialization. The feeling was palpable: the U.S. fusion industry is at a critical juncture.

The race is on. The next few years will be crucial in determining who leads the world in fusion energy. It’s a race with vast implications, one where technological prowess and strategic foresight will determine the winners.