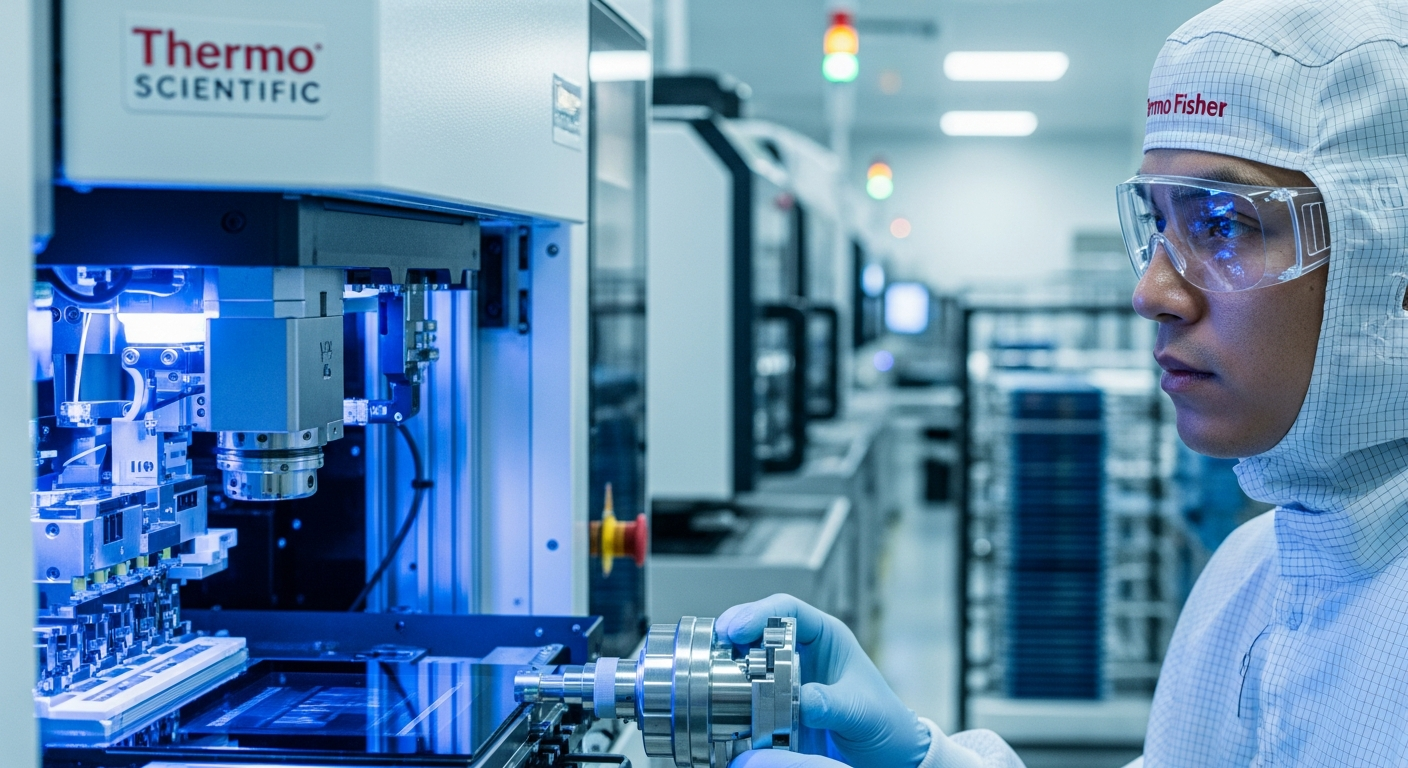

The hum of the ASML scanner filled the cleanroom. Engineers, clad in bunny suits, hunched over monitors, scrutinizing wafer maps. It was just another Tuesday at the Bengaluru facility, but the stakes felt higher. India’s semiconductor ambitions were on the line, and Thermo Fisher Scientific, a key player in the global supply chain, was betting big on the country’s potential.

According to Thermo Fisher leaders, India has a unique opportunity to compress the learning curve. By embracing advanced analytical tools early in the process, developing a skilled workforce upfront, and fostering close collaboration with global ecosystems from day one, India could scale its semiconductor manufacturing faster than expected. The core idea is to leapfrog some of the more painful, iterative processes that have characterized the industry’s evolution elsewhere.

“India’s approach is fundamentally different,” says a senior Thermo Fisher executive, speaking on condition of anonymity. “It’s about accelerating the learning cycle. Instead of waiting, they’re going all-in on the most advanced equipment and methods, right from the start.” This strategy is in stark contrast to the incremental approach taken by some established players, and it reflects a broader trend of rapid technological adoption in the country.

The company’s optimism isn’t unfounded. India’s domestic semiconductor market is projected to reach $30 billion by 2026, according to a recent report by Deloitte. This growth is fueled by increasing demand for electronics, government initiatives like the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, and a growing pool of skilled engineers. The PLI scheme, for example, offers financial incentives to companies that set up semiconductor manufacturing units in India, effectively lowering the cost of entry and encouraging investment.

But the path isn’t without its challenges. The global semiconductor landscape is fiercely competitive. Export controls, supply chain constraints, and the complex manufacturing processes present significant hurdles. For instance, the availability of advanced equipment from companies like ASML is limited, and securing these tools requires navigating complex geopolitical considerations. The success of India’s semiconductor push will also depend on its ability to build a robust ecosystem of suppliers and partners, as well as fostering innovation within the country.

Thermo Fisher’s perspective is crucial because its analytical tools are essential for quality control and process optimization in semiconductor manufacturing. Their technology helps identify defects, improve yields, and ultimately, reduce costs. By integrating their tools early in the manufacturing process, India could potentially achieve higher quality and efficiency, accelerating its progress. It’s about getting it right the first time, or at least, getting it right faster.

The implications are significant. If India succeeds in scaling its semiconductor manufacturing capabilities rapidly, it could become a major player in the global market, reducing its reliance on imports and boosting its economy. It also means more opportunities for local engineers, a stronger technology ecosystem, and a more resilient supply chain. The question is, can India execute this ambitious plan? And the early signs, from the humming cleanrooms to the projections, suggest that the answer is a qualified yes.